Brooklyn, around noon, on a summer day.

At first I felt sorry for the man who was hit by the subway train. Then annoyed. The police hoisted the bloodied fellow out of the station on a stretcher up to street level and into an ambulance. The requisite police investigation meant I couldn’t get into the station to take the train back to my apartment in Chelsea, and the nearest station was on Eastern Parkway, a healthy distance away. What the hell, I’ll walk.

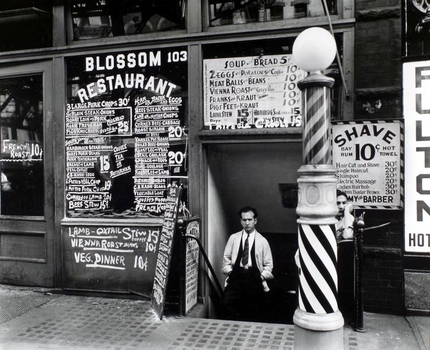

I hoofed it up Nostrand Avenue and began to notice that what used to be a white, mostly Jewish neighborhood had morphed into Caribbean turf. Now, there were signs in the windows of fast food joints advertising Goat Roti in place of the pastrami sandwiches of my youth. The food always changes with the neighborhood. I was in strange territory, but I was unaware of how strange things were about to become.

Nostrand Avenue was a street, a name that I knew practically from birth. It was one block away from, and ran parallel to the street I grew up on. It was where my mother and grandmother shopped before shopping became a car trip to the supermarket. It was where I saw a woman sitting in the window of the kosher butcher shop plucking chickens. Now, as I walked up Nostrand toward the subway station the names of the cross streets sounded more and more familiar. Then I reached Empire Boulevard and entered my own personal twilight zone.

Oh my God! Empire Boulevard, the southern-most border of my childhood. I hadn’t been on these streets in decades, maybe not since 1959 when my family moved to Canarsie. Now without any mental preparation I was suddenly and inexorably compelled to walk the streets that were the playground of my youth-the streets of Crown Heights. There was a ten-year-old boy inside of me pushing me toward the old streets, pushing me back in time.

The ten-year-old boy and I turned right and walked quickly along Empire until we came to New York Avenue-my street. The memories, call them distant voices, started coming immediately as soon as we turned up New York and hit Malbone Street. This was a dirt road, a one-block affair probably left over from pre Civil War days. It ran past the Hebrew school I attended and ended at an open lot. One day Robert Stillman and I tried to use that lot as a launch site for a homemade rocket. The Soviets had just boosted Sputnick into orbit and the dreams of many a young lad went along for the ride. Robert, a bright, pudgy kid with an intoxicating cynical streak, got hold of a recipe for gunpowder, our rocket fuel of choice. I supplied a shell casing from a 38-caliber police special revolver. My father, a Jewish NYC cop, brought these shell casings home for me to “fool around” with. They were harmless and made great whistles if you knew the right way to blow across the open end. Robert and I though it would also make a great rocket since it was already familiar with the presence of gunpowder. We snuck into the lot in broad daylight, filled the shell casing with Robert’s homemade gunpowder, stood it upright on a rock and attempted to light it. Nothing happened. We tried again. Nothing. Apparently, Robert needed a few more chemistry lessons. Soon, a lady from an adjacent apartment house leaned out of her window and screamed at us, calling us crazy kids. We ran. In my memory, Robert is still running. We parted ways soon after the failed rocket incident.

I couldn’t leave the intersection of Malbone and New York without thinking about Beth David Gershon. This was not the name of a girl. It was the name of my Hebrew school. I could still imagine the waxen glow of the red, blue, green, and yellow Hanukkah candles in the windows of its classrooms burning with an intensity seen only by the very young. I saw my teacher, Rabbi Rubin, a youngish fellow, a chain smoker who was comically nervous, sort of a Jewish version of Don Knotts. I was standing outside of the front entrance under the canopy and the Rabbi was walking toward me. I had just beaten up the most obnoxious kid in the school and I thought, “Uh oh, The Rabbi’s gonna call my parents!” Instead, the Rabbi, this man of peace, this man of God, extended his nicotine-stained hand and congratulated me for kicking the kid’s ass. I guessed at the time that giving this kid a beating was something the Rabbi had longed to do himself but couldn’t for rabbinical reasons. There were other Hebrew school voices, but the boy inside me was pushing me further up New York Avenue.

Soon we came to New York between Montgomery and Crown Streets. A voice emerged from an apartment house across the street. It was Richard. For a time we hung out together, played little league, newcomb (a form of bastardized volleyball), and worked on the same school projects in the fifth grade. He was a big kid, the kind of kid that parents think is a ringer at softball games-“he can’t be twelve, look at the size of him!” He was a leader and made things happen. And he was smart. He was also a lousy second baseman, a fact that did not sit well with his oversized ego. I recently heard his name on National Public Radio. Dr. Richard Axel had just been awarded the 2004 Nobel Prize for Physiology and Medicine. I guess he made up for being a lousy infielder.

Another voice emerged from that block, Pasquale Fiorelli. Like Axel, he too was the son of immigrant parents, but that’s where any and all similarities ended. Pasquale was an Italian street kid, not the kind you see in local gangster films, but the kind that survived on the ravaged streets of Italy after WWII. He worshiped his older brother whom he claimed was a great artist. Funny how this street tough valued art. This enabled us to make a connection, as I, too admired people who could draw and fancied myself an artist. Pasquale joined us as I and the boy inside me headed up New York Avenue and turned left on Crown Street.

The siren song of the schoolyard was calling us to PS 161, my alma mater. No sooner did we stand at the schoolyard gate when Pasquale was inside attacking Robert VanHayva, the bully who strode the schoolyard like Godzilla destroying all in his path. Rumor had it that he belonged to the Pig Town gang, I later learned that Pig Town was the local name of the garbage dump on Bedford Avenue where Ebbetts Field was later built. Before the Brooklyn Dodgers played there feral pigs patronized the dump as their favorite restaurant. Back in the schoolyard of my youth the very mention of Pig Town made most of us boys freeze with fear. Not Pasquale. Although he was of average size, he was stronger, could run faster, and punch harder than anyone I knew. And he was my friend, thank God. But how could even Pasquale beat Godzilla, a monster that stood at least a head taller than him. Simple. One day, in the schoolyard, he challenged VanHayva and literally climbed up the bigger boy and punched him in the mouth. That day Pasquale taught us all the difference between swagger and tough.

We can’t leave the schoolyard just yet. Not before Robert Stillman reappears carrying something even more explosive than gunpowder-pictures of naked women. It figured that Stillman would be the kid to get hold of Playboy magazine. It’s what he did with it next that was so memorable. With the centerfold wide open, he walked right up to a group of girls, pushed it in their faces and said, “See this, this is how you’re gonna look some day!” How the hell did he know that? This was a stroke of schoolboy bravado on an unprecedented scale. It was one thing to show your pals pictures of tits, but to show it to girls! Their reaction was a combination of shock, fascination, disbelief, and disgust, sort of the same reaction as if Stillman had put live frogs down their backs. He had cracked the “girl code” and gotten around their defenses. Only a person in league with the devil could have been devious and clever enough to use pictures of naked girls as a weapon against-girls! So much for Nobel prizes; where was Stillman’s prize!

Goodbye Pasquale, goodbye Stillman, goodbye schoolyard. Back to New York Avenue. The boy and I headed up the hill past lovely limestone townhouses toward New York and Carroll. What’s that up ahead? It looks like the back of a boy I know. It’s Murray Pessin! Murray was a year or two older than me and had a reputation for being sneaky. That, plus the fact that he looked vaguely Asian got him the nickname, “The Jap.” It was, after all, the late 50’s not long after WWII so Jap was a perfectly acceptable moniker, except for the person who was tagged with it. This day would give Murray his new nickname. When I originally saw him he was walking toward me, and he was bleeding! I was walking down New York Avenue on my way to Hebrew School when, half a block away, I saw him, arms hanging at his sides dripping blood from dozens of small red wounds. His eyes looked dazed and glassy, like the eyes of the dead fish I used to see in the window of the fish store on Nostrand Avenue. When you’re a kid and you’re hurt bad you instinctively head for home, if you can still walk. Murray was headed home. They said it had been a test tube full of nitroglycerin that he mixed up from his chemistry set that exploded in his hands. They said he made the mistake of shaking it. At least that was the story. I didn’t stop Murray to ask for the details. In fact, I didn’t stop at all. I was late for Hebrew school. That was the excuse I gave Murray’s mother when she scolded me for not running back home immediately to tell her what happened. What was her problem-he was walking and he was heading back to the apartment house where we both lived. Grownups!

Murray healed physically, but ever since that day he was known as the “mad bomber,” an honor he shared with George Metesky, the official mad bomber of the 1950s, a man who was, in retrospect, way ahead of his time. We used to think of Murray as smart, but now he was just crazy, someone to avoid. After all, who knew when he might bump into someone and explode. The last I heard of him he and a friend had been caught shoplifting. The friend’s parents forbade him to ever see Murray again. It’s lonely when you’re a mad bomber.

Part Two

The nostalgia duo–I and the boy inside–approached President Street, the street of dreams. Real honest-to-goodness mansions lined President between New York and Brooklyn Avenues. One of my friends lived in a 26-room villa, and he even had his own gym. I played ball with Bobby Steingut who lived on that block. He was the son of Stanley Steingut, majority leader of the New York State senate. Martin Luther King reportedly recuperated in one of those mansions having recently been stabbed by a crazy woman wielding a pen-it was an omen of things to come. But the voice on this trip didn’t come from the mansions. It came instead from the basement of one of the apartment houses on the corner of President and New York. It was the voice of Jesse Bannister.

Jesse was one of the black kids in the neighborhood. There were many black kids, mostly children of middle and upper class blacks who had moved across Eastern Parkway to escape the crime in Bedford Stuyvesant. In fact, Crown Heights in those days was the Bizzarro-world of race. We white kids lived in aging apartment houses while most of the black kids I knew lived in brownstones. My landlord was Haitian, and I played with his son, Mickey Small. More about that later. It was Jesse’s voice I was hearing.

Jesse was the son of a superintendent, or “super” as we called them; a janitor to you foreigners. All the supers on the adjoining streets were black and lived an underground existence in the basements like Warlocks. Jesse’s dad was a skinny, old man with one eye that looked in the wrong direction. And he was fiercely proud, an attitude which caused him to keep a tight rein on Jesse. We found this out one Halloween.

Halloween. What a scary, crazy, wondrous day. Anything could happen. Kids would fill socks with hard pieces of the large pastel chalk and pulverize it by hitting other kids over the head. Others would chalk up sticks and whack you with them until you cried or laughed, or both. And then there was trick-or-treat, the scariest, most exciting part of the day. This was the time before mothers gave a second thought to allowing their children to go in to strange buildings by themselves and knock on strangers’ doors. To be sure, there were the rumors of apples with the razor blades inside. But I never saw one. All us kids were turned loose, except for Jesse. His dad would not hear of it. I did not understand why until my best friend Allen Brand and I knocked on a door in Jesse’s building. A lady answered, not with candy or money, but with a scolding: “Jesse wouldn’t go around trick or treating! His father wouldn’t let him go door-to-door begging like you boys!” Begging! So, that was it. To Jesse’s dad Trick-or Treat was nothing but begging. All at once a lot of history became clear to me. Unlike our middle class white fathers, Jesse’s dad had to claw his way out of the dungeon of racism and had risen to the status of building superintendent. He worked hard and earned every damn penny; he was independent and free. No son of his was going to be a beggar-or a super for that matter! Call it anything you like, Trick-or-Treat was begging. It was fine for a bunch of wild white kids to be asking for handouts, but as soon as Jesse stuck out his hand he would be branded as “that little black beggar.” I felt bad for Jesse because I knew he just wanted to be a kid like all the other kids, not a symbol or a martyr. As I walked past the corner of New York and President I wondered if Jesse ever made it up and out of the basement. I wondered if he would let his kids go Trick-or-Treating.

I crossed President and stepped on to the block where I was born. The little boy did not have to push me now. I walked past the intersection where a car spun out of control and dumped its dead driver in the gutter in front of us kids. My mother heard the screech and the sound of metal slamming into metal and rushed down two flights of stairs to see if that terrible noise was her worst nightmare, her son run over by a car. It wasn’t. I walked passed the spot where we poked a dead cat with a stick to make sure it not playing some sort of trick, as everyone knew cats were wont to do. It looked strangely like the dead driver.

Lenny Lamont, one of the bad Irish boys from Union Street decided that this cat needed a proper burial. So, he picked it up by the tail and a bunch of us marched around the corner and into the yard of the brownstone next to my apartment house for the funeral service. Lenny pulled a pair of the homeowner’s underwear off the clothes line, wrapped the cat in it, dug a hole in the garden and dumped the poor dead thing in to its final resting place. Then he yanked some flowers out of the garden and laid them on the grave. A touching ceremony, really. Then for good measure, he ascended the steep stairs that led to the kitchen door of the brownstone and tipped over a metal garbage can spilling all of its rotting contents on the stairs and in the yard. We ran like hell.

A chorus of voices were coming to me now on this block. There was crazy Jimmy, the retarded older brother of the kid across the street. We taunted him without mercy and made him do the crazy sign by his ear-what jerks we were. There were the Rays, a shanty Irish family that was dirt poor and glad to be living in a “rich” neighborhood. Ronnie Ray told us the story of how his rectum was crushed by a car that had run him over. We had never heard stuff like this.

Then there were the Levits, a family of true lunatics. It was rumored that the father had gone to Harvard but was now a junk man. The mother was a paranoid schizophrenic who would threaten to sue anyone that looked at her cross-eyed. One day, Julie, the oldest of the three kids took us in the back yard and down the basement steps to “show us what girls have.” After she finished her “show-and-tell” she said it was our turn to show her what boys have! We all started to run, our legs feeling like they were stuck in cement. Julie was big and fast, and I think she caught one or two boys. I didn’t stick around to find out. By far the craziest of the Levit bunch was Gary, the middle child. His growth was stunted by diabetes and he looked seven though he was really eleven. I once accompanied him on a walk around our block as he sung Yiddish begging songs, an old tire slung over his shoulder for dramatic effect. Gary was the one who instigated the “back yard wars” during which time the Levit kids would toss toys-some of them metal-out of their windows at the kids below as if defending a medieval castle under siege from invading Visigoths. We responded by throwing stuff back up at the Levits. I happened to have a very good pitching arm and hit the youngest Levit boy in the head with a large, rusty steel nut. They pulled him away from the window bleeding from his forehead, the first casualty of the back yard wars. But by far the craziest thing I ever saw Gary do involved one of the ultra orthodox Jewish boys that lived in his building. Gary sat the kid down in the Levit kitchen and proceeded to hypnotize him using a piece of an Erector Set as a wand! I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. I know it wasn’t a trick because Gary heated the makeshift wand on the stove and branded the kid with it! The kid didn’t flinch.

I saw my friend Mickey Small, the son of my Haitian landlord playing his favorite game in front of my apartment house. He would crouch down in a runner’s stance between parked cars and then, at the very last minute, he would dash across the street in front of a car speeding up New York Avenue. I wonder if he ever made it to adulthood.

Now I was looking across the street and my father and my three-year-old sister. He has just handed her off to a neighbor and he is running like a man with his hair on fire. I, and my best friend, Allen Brand, have just been run over by a panel truck. The driver was delivering clean laundry to the tailor’s shop and he came to the intersection New York Avenue and Union Street only to find that he could not turn left on New York. So, instead of going around the block, he backed his truck around the corner just as Allen and I were crossing to go to the candy store. Since he was coming from the wrong direction we never saw him and the next thing we knew Allen and I were under the truck. We got up and ran across New York Avenue purely by instinct. Luckily there was no other traffic or surely we would have been hit again, maybe even killed. I peed in my pants but, miraculously, only my dignity was hurt. A few inches in either direction and the truck’s wheels would have squashed us. My father, the tailor, the truck driver, and I all assembled in the tailor’s shop. The driver started making some lame excuses to cover up for his negligence when the tailor informed him that my father was a cop. A look of fear immediately settled on the driver’s face and he had no more to say. The incident came to closure a few weeks later when, at our lawyer’s office, I was coached in the fine art of lying: “Say your back hurts if they ask you.” The only thing that hurts now is the painful memory of a tragedy that might have been.

Allen Brand also escaped injury, but that’s where his luck ended. I looked up New York Avenue one block to Eastern Parkway, the scene of the worst incident of my childhood. Allen was an only child. His father had been, it was said, a Hockey star in Canada, unusual for a Jewish man. He was a jeweler by trade and wore Coke bottle glasses, his eyesight having been ruined by years of close work. His mother, a nurse, was a quiet woman who made us Kool-Aide to drink on hot summer days. One morning, when I was twelve, we got the news. Allen’s parents had been run over by a hit-and-run driver while crossing Eastern Parkway on their way back from temple. His dad was dragged for blocks and died at the scene. His mother survived, but spent six months in the hospital. She was never the same. As a child I did not see the irony that now occurred to me: Two god-fearing people coming back from a prayer session mowed down in the gutter as if they had deserved punishment for some horrible deed. We went to visit Allen who was temporarily living with his aunt. He wore a black ribbon, which I did not understand at the time was the torn ribbon of the mourner. I had never seen a mourner before, let alone one my own age. This incident was really the end of innocence, innocence ground into the gutter by a coward behind the wheel of a car. If Allen’s parents could be cut down, were we not all vulnerable? I moved away from Crown Heights shortly after this dark day.

I was now at the northern border of my childhood, the end of my time travel. I turned on Eastern Parkway and headed for the subway alone, the boy inside me having chosen to remain where he belonged, in the past. Once again I was leaving Crown Heights, but Crown Heights will never leave me.

Crown Heights Chronicles

(c) 2005 By Howard R. Roberts

All rights reserved.