The design of decline

I was grocery shopping on a Friday night—I’m at an age when not only is that normal but admitting to it doesn’t bother me—and I noticed something new.

There were gates on a few of the aisles. Posted signs mentioned that the aisles would be closed after 7 p.m. and that customers could request they be opened. I was sure I knew why the gates were there, but I asked a store employee anyway. As I expected, he answered, “Too many people stealing.”

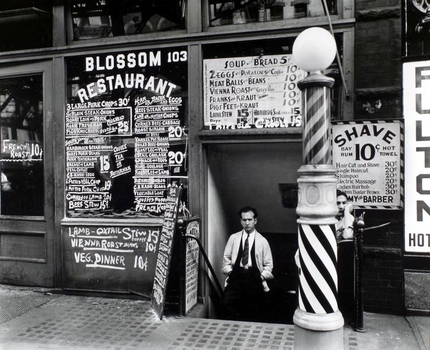

These kinds of gates are old news in many parts of the country. In most drug stores and convenience stores, high-theft items are already under guard, with alarm-trigger glass cases housing razor blades and cold medicine.

Over the past year, I’ve seen more shoplifters apprehended at this store than in the previous 10 years combined. In one case, there weren’t enough store security people to apprehend two men who had massive helpings of chicken hidden under their clothes, so the one lone guy made sure they dropped what they were stealing before letting them walk away. The would-be thieves sauntered through the parking lot, completely unconcerned that they would be arrested, not caring who saw them.

Across cultural and political divides, there is a sense in the U.S. that as a society, we are going out of our way to tolerate the intolerable. The percentage of the population that commits crimes may be small, but the gates on grocery aisles is a way that we all pay.

Everywhere the world around us bears the marks of our acceptance of the unacceptable and designing our environment in ways that are an acquiescence to societal problems. Park and subway benches have awkward dividers and ridges to prevent homeless people from sleeping on them rather than allowing people to sit on them comfortably. Many fast-food restaurants have no public restrooms, lest they attract homeless

In many ways, these elements of design indicate that we’re failing collectively. We are accepting the unacceptable because we don’t see a way out and we don’t feel a collective responsibility to the world around us. A collection of forces has chipped away at the collective “us.” When there is no “us,” no “we,” there’s not a common glue to the everyday world.

When we don’t feel connected to the community around us, we don’t take action to improve that community. People aren’t working together to solve their common problems; they are doing what they can to keep themselves away from the worst parts of the herd. They are covering their asses, and doing only their part.

People are starting to resist this spiral of decay. Customers are stopping shoplifters on their own when store employees are not allowed to. Even at my local grocery store, the last time I asked for the gates to be unlocked so I can buy some soap, the store employee told me that the gates were already unlocked, and that I should just close them behind me when I left.

Slowly but surely, if we regain our collective will, we can reverse our decline and make this design of decline a thing of the past.